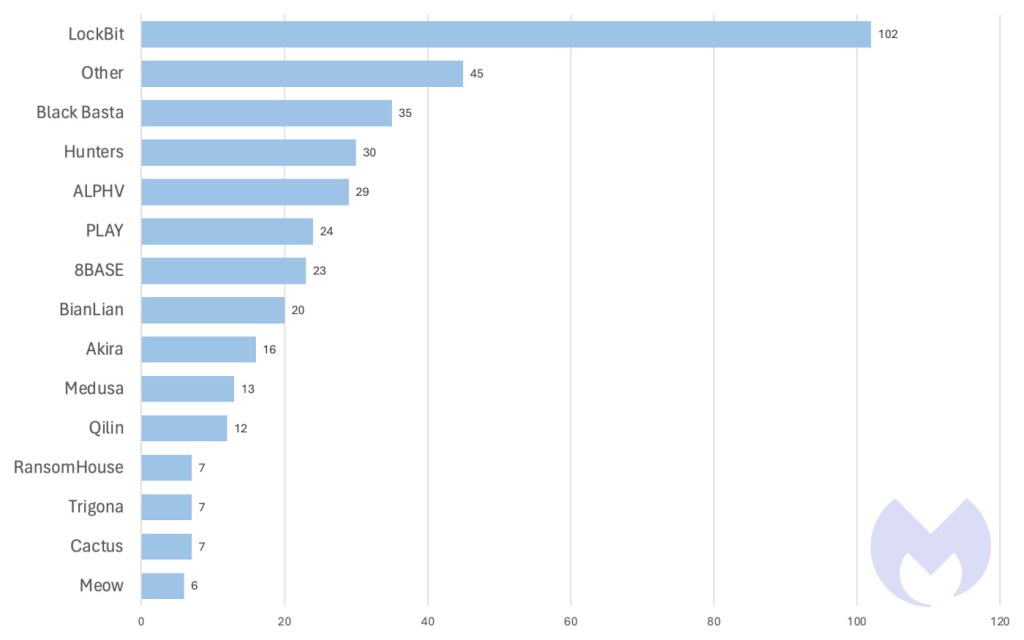

This article is based on research by Marcelo Rivero, Malwarebytes’ ransomware specialist, who monitors information published by ransomware gangs on their Dark Web sites. In this report, “known attacks” are those where the victim did not pay a ransom. This provides the best overall picture of ransomware activity, but the true number of attacks is far higher.

In February, there were 376 ransomware victims, marking an unusually active month for the historically subdued time period. But February didn’t just bring unprecedented numbers, but unprecedented developments as well: law enforcement shut down LockBit, the largest ransomware gang, while ALPHV, the second-largest, appeared to fake its demise and abscond with its own affiliates’ funds.

Before we dive into the two biggest stories of the month, however, let’s start with a quick overview of other significant ransomware developments, including a new Coveware report revealing a record low of 29% of victims paying ransoms in the last quarter of 2023.

A few years ago, paying ransomware attackers was almost a given—85% of hit organizations in early 2019 felt they had no choice. But fast forward to 2024, and Coveware data suggests that that trend has completely reversed—not only have the number of victims paying dropped but so have the dollar amounts of actual ransom payments. In other words, we’re seeing fewer and smaller ransomware payouts than ever before.

At first glance, the trend appears counterintuitive: with global ransomware attacks hitting record highs annually, one might expect a proportional increase in the number of victims choosing to pay a ransom. But as it turns out, all the attention on ransomware is effectively shooting attackers in the foot: the more these attacks make headlines, the more businesses understand ransomware as a prime threat, leading to improved security measures that can allow victims to recover from an attack without paying a ransom. Also discouraging payments are increasing doubts about cybercriminals’ reliability and stricter anti-ransom laws.

But all of this begs the question: with fewer payments, will ransomware gangs adapt their strategies to remain a threat, or will the decrease in successful ransoms lead to a decline in attacks as they seek more lucrative avenues? Will ransomware attacks always remain profitable, albeit less so over time? The report raises just about as many questions as it answers.

Our prediction? Ransomware gangs aren’t backing down any time soon; in fact, they’ll likely continue getting more inventive in pressuring companies to pay up. Our coverage on “big game ransomware” showed ransomware gangs aren’t just hiking up demands when companies resist paying, they’re also turning to more aggressive tactics. “Threats to leak data, sell it online, break other parts of the business, attack related firms, or even harass employees are all tactics gangs can make use of” to force reluctant businesses to pay, writes former Malwarebytes Labs author Christopher Boyd.

In other words, despite fewer companies paying up, we foresee ransomware attackers compensating with higher ransom demands and more sophisticated, aggressive negotiation tactics.

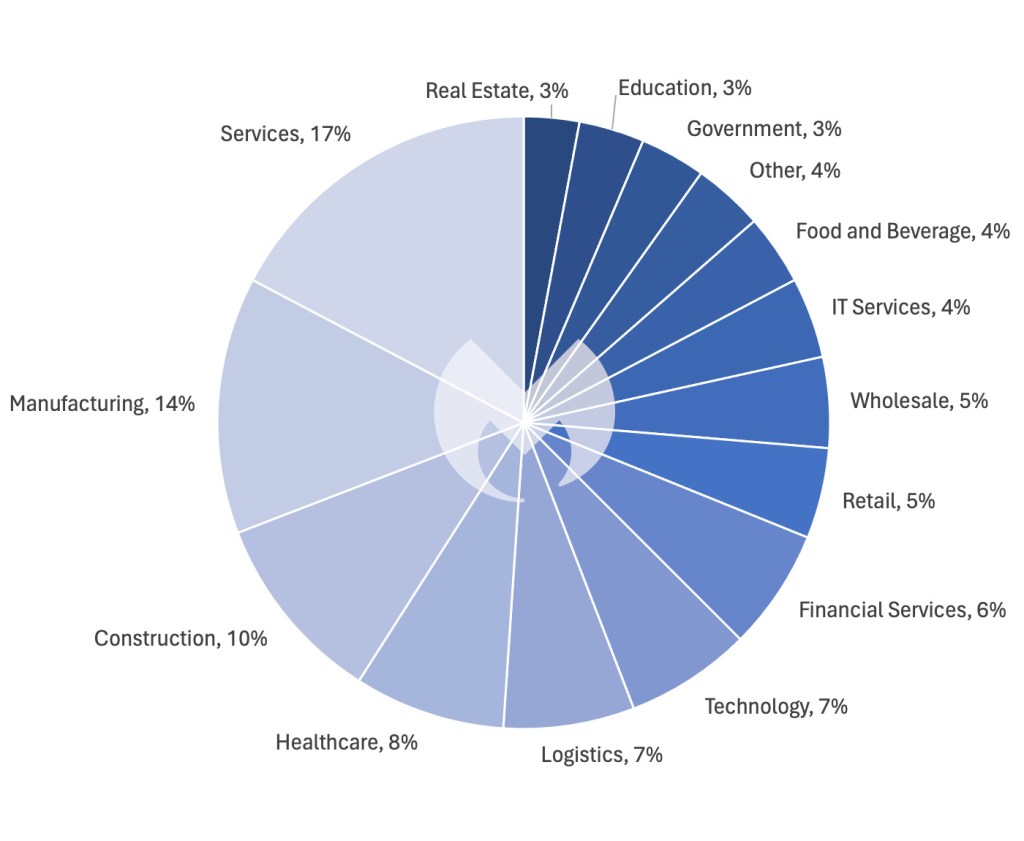

In other February news, new reports highlighted ALPHV’s surge of targeted attacks against the healthcare sector. Coincidentally, a day after these reports were published, there was news of ALPHV’s severe attack on Change Healthcare, one of the largest healthcare technology companies in the US.

The report indicated that since mid-December 2023, out of nearly 70 leaked victims, the healthcare sector has been ALPHV’s most frequent target. This seems to be a response to the ALPHV Blackcat administrator’s encouragement for its affiliates to target hospitals following actions against the group and its infrastructure in early December 2023.

The Roman historian Tacitus once said, “Crime, once exposed, has no refuge but in audacity.” Well, the exposure of ALPHV’s crimes has seemingly emboldened them further, pushing them to undertake even more brazen acts of revenge against the very institutions aiming to curb their criminal activities. At the end of the day, ALPHV’s actions are unsurprisingly petty, pointless, and endanger human lives, but they at the very least they hint at the group’s last desperate gasps for relevance.

On the vulnerability front, ransomware gangs like Black Basta, Bl00dy, and LockBit were seen exploiting vulnerabilities in ConnectWise ScreenConnect last month that exposed servers to control by attackers. It appears that almost every other month, our ransomware reviews uncover a new vulnerability being exploited with great success—whether it was MOVEit in the summer of 2023 or Citrix Bleed at the end of 2023. The vulnerabilities in ScreenConnect are once again part of this broader trend we’ve noticed of ransomware gangs finding ever-new points of entry—perhaps even more quickly and extensively than in previous years.

LockBit down, ALPHV out

February 2024 is likely to be remembered for years as the month when two of the most dangerous ransomware gangs in the world suffered some serious turbulence.

LockBit has been the preeminent ransomware menace since the demise of Conti in spring 2022, but for the first time there are serious reasons to doubt its status and longevity. On February 19, the ransomware gang’s dark web site announced “This site is now under the control of The National Crime Agency of the UK, working in close cooperation with the FBI and the international law enforcement task force, ‘Operation Cronos’.”

What followed was something quite unique in the annals of ransomware takedowns. Alongside the usual dry press releases, the law enforcement agencies responsible used the site it had acquired to showcase the details of what it had done.

It was an act of exquisite trolling that looked designed to damage the LockBit brand by humiliating it in the eyes of its peers and affiliates.

There was substance to the disruption too—some arrests, “a vast amount of intelligence” gathered, infrastructure seized, cryptocurrency accounts frozen, decryption keys captured, and the revelation that LockBit administrator LockBitSupp “has engaged with law enforcement.”

LockBit quickly established a new site and insisted everything was fine in exactly the way that people do when things aren’t fine, by releasing a stream of concious 3,000-word essay that explained precisely how fine things were, thanks. It remains to be seen if LockBit’s rebound will last. When ransomware gangs start to feel the hot breath of law enforcement on their neck a rebrand normally follows.

LockBit’s main rival, ALPHV, used February to demonstrate an alternative ending. It decided to leave the ransomware world behind by ripping off its own customers (which are really just affiliates in crime) in a sloppily executed exit scam. ALPHV had suffered its own brush with law enforcement in December and, like LockBit, appeared to have recovered.

Perhaps it was spooked by its brush with the feds, or perhaps the $22 million ransom an affiliate extracted from its devastating attack on Change Healthcare was just too hard to resist. Whatever the reason, ALPHV cut and ran, taking the cash and leaving its criminal affiliates high and dry. A half-hearted attempt to pin the blame for its disappearance on the FBI fooled no one.

Preventing Ransomware

Fighting off ransomware gangs like the ones we report on each month requires a layered security strategy. Technology that preemptively keeps gangs out of your systems is great—but it’s not enough.

Ransomware attackers target the easiest entry points: an example chain might be that they first try phishing emails, then open RDP ports, and if those are secured, they’ll exploit unpatched vulnerabilities. Multi-layered security is about making infiltration progressively harder and detecting those who do get through.

Technologies like Endpoint Protection (EP) and Vulnerability and Patch Management (VPM) are vital first defenses, reducing breach likelihood.

The key point, though, is to assume that motivated gangs will eventually breach defenses. Endpoint Detection and Response (EDR) is crucial for finding and removing threats before damage occurs. And if a breach does happen—ransomware rollback tools can undo changes.

How ThreatDown Addresses Ransomware

ThreatDown bundles take a comprehensive approach to these challenges. Our integrated solutions combine EP, VPM, and EDR technologies, tailored to your organization’s specific needs. ThreatDown’s select bundles offer:

- Advanced Web Protection: Blocking phishing websites ransomware gangs use for initial access.

- RDP Shield: Securing remote access points with Brute Force Protection.

- Continuous Vulnerability Scanning and Patch Management: Identifying and patching weaknesses before ransomware gangs can exploit them.

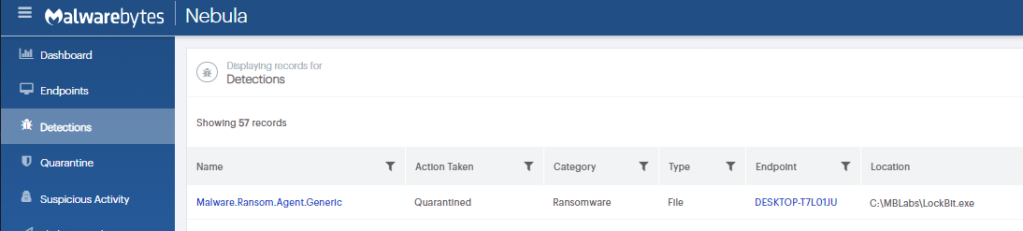

- Sophisticated EDR: Detecting and neutralizing advanced threats such as LockBit within the network.

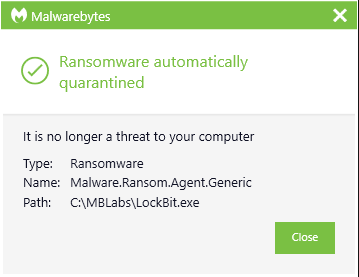

- Ransomware Rollback: Reversing the impact of any successful attacks.

ThreatDown EDR detecting LockBit ransomware

ThreatDown automatically quarantining LockBit ransomware

For resource-constrained organizations, select ThreatDown bundles offer Managed Detection and Response (MDR) services, providing expert monitoring and swift threat response to ransomware threats—without the need for large in-house cybersecurity teams.

Our business solutions remove all remnants of ransomware and prevent you from getting reinfected. Want to learn more about how we can help protect your business? Get a free trial below.

Read more https://www.malwarebytes.com/blog/threat-intelligence/2024/03/ransomware-review-march-2024